The Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick Award presented by Dr Pepper will be given annually by the Charlotte Sports Foundation (CSF) to a senior football player from Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) who displays talent both on the field and a passion for their community. The award, which comes with a $10,000 scholarship, trophy and recognition at the Duke’s Mayo Bowl, is named after Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick of Myers Park High School.

Each fall, the 19 public high schools of CMS will select their semi-finalists for the award to represent their school on the field at the Duke’s Mayo Bowl. From those individuals, one winner will be announced and will receive a scholarship, in addition to the trophy that will be displayed at their school for the following year. The trophy, which is a bronze bust in the likeness of Kirkpatrick, will be inscribed each year with the winner and their high school.

A panel of representatives from the CSF, CMS and the community will select the winner each year from the nominees provided from the schools. Equal weight will be placed on athletic achievement and community impact with the overall goal of recognizing individuals who match the character and passion as the award’s namesake.

Award Winners

2021 – Jeremiah Burch JR, Olympic High School

2022 – Michael JJ Coleman, Butler High School

2023 – Phillip Harris, Butler High School

2024 – Cameron Cyr, Hough High School

2021 Winner: Jeremiah Burch Jr – Olympic High School

“I am honored to be a part of this award and excited about the recognition it will offer young athletes. I was always encouraged to take risks and dream, even though the recognition and the path to success wasn’t there for Black athletes in my day. When I did receive honors, I was inspired and saw doors opening – for myself and others. I hope the students receiving this award will feel similarly inspired for the recognition of their personal character and for the impact that they are making in their communities.” – Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick

“When we first thought of this award we knew Jimmie would be an incredible person to name it after. He not only is one of the greatest players in Charlotte football history, but he endured so much with positivity and steadfast determination. He is a trailblazer in every sense of the word and we hope his story continues to inspire generations of Charlotteans.” – Danny Morrison, executive director of CSF

About Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick

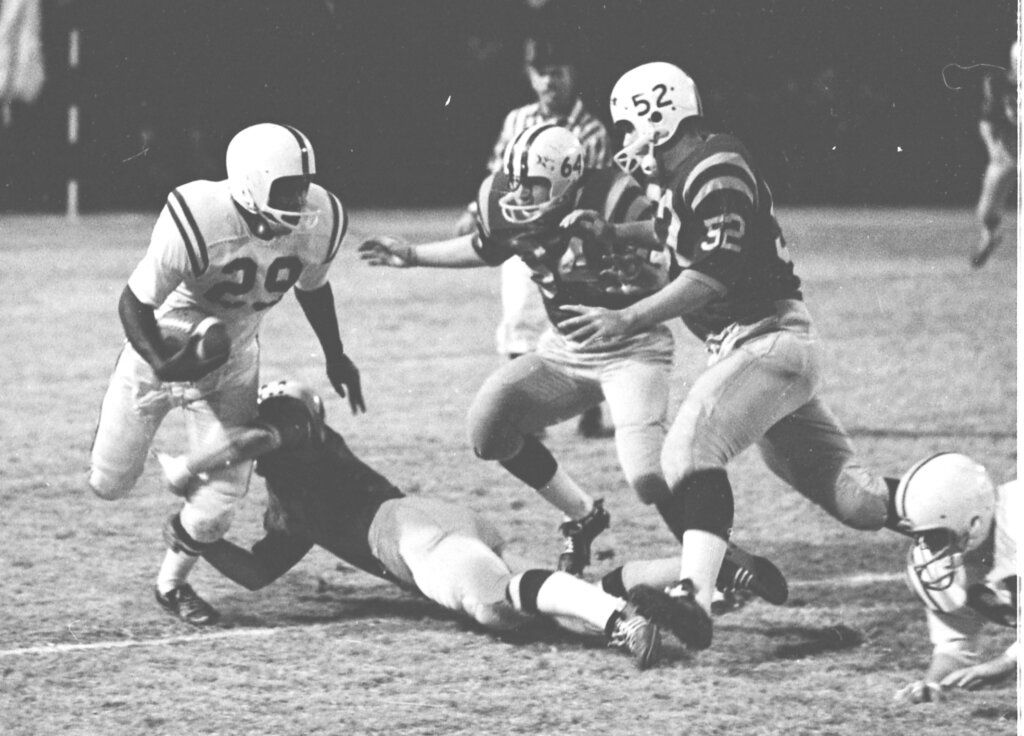

In 1965 Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick made the brave decision to leave Second Ward High School to play for the predominantly white Myers Park High because of the opportunity it allowed him on the field as well as for the chance to open doors for other Black students to have access to better academic and athletic opportunities. That fall, Kirkpatrick was magic with the ball in his hands, accumulating 19 total touchdowns and All-American honors, all the while being subjected to hostility and open racism on the playing field and in the community.

The Mustangs finished the year undefeated and Kirkpatrick was named the best player in Charlotte and nominated to play in the Carolina’s all-star game, the Shrine Bowl. At that time the game had not been desegregated and Kirkpatrick was snubbed from the team, resulting in a public outcry and a lawsuit filed by legendary civil rights lawyer, Julius Chambers.

A judge ruled that the game could go on but future Shrine Bowls must be integrated. Within days, the homes of Chambers and three other civil rights leaders were bombed in Charlotte. Police interviewed more than 50 people, including Ku Klux Klan members, but the case remains unsolved. In 1966, two Black players were named to the North Carolina Shrine Bowl team. By then, Kirkpatrick had moved on to play football at Purdue and later settled in Oregon, where he worked as an educator and continued to push for equal rights.

His story was largely forgotten in Charlotte, until it was told in a 2013 Charlotte Observer series by Gary Schwab, David Scott and David Foster called “Breaking Through.” In response to that series, Kirkpatrick was reunited with former classmate De Kirkpatrick. The two learned that De’s great-great grandfather had enslaved Jimmie’s great-great-great grandfather in the 1860s. Together, they now speak to groups about their personal journey into understanding their past, and about racial justice.

For more information or media inquiries contact Miller Yoho.